Illustrations and further background material

Illustration 1.

Illustration 2.

Illustration 3.

Illustration 4.

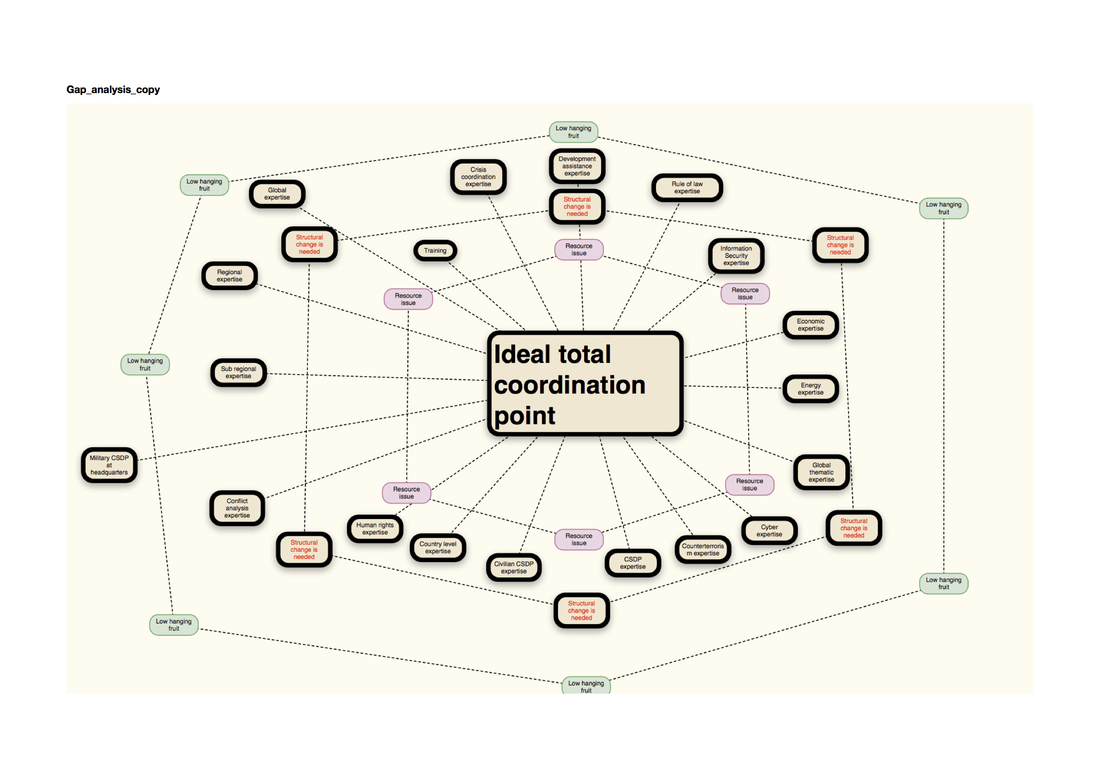

Illustration 5: Example of gap analysis concerning necessary expertise for both cases

illustration 6.

Illustration 7.

Brief summary available research on radicalization:

- Extensive research has been carried out in the last decade on the steps towards recruitment of terrorists. In brief summary the literature speaks of three main developments: the accumulation of grievances, the development of an ideology (religious or political) and the mobilisation phase towards a preparedness to undertake or participate in terrorist acts.

- Sophisticated network analytics have demonstrated that the process of linking the perception of grievances to ideology and then again to a willingness to be mobilised often is entirely taking place in formally legal ways. The religious or political leaders do not themselves have to participate in illegal action. The actual preparation and carrying out of terrorist acts do not have to have anything to do with the process of delivering human resources.

- This of course makes the task of law enforcement very difficult and points to the need for preventive strategies implemented also in other formats than law enforcement.

- Intelligence efforts are however, according to the literature, likely to be particularly successful when focusing on the third stage, mobilisation. It has been shown in case studies that the presence of extremist religious or political leaders in a community is strongly correlated with the recruitment of terrorists.

ILLUSTRATION 8.

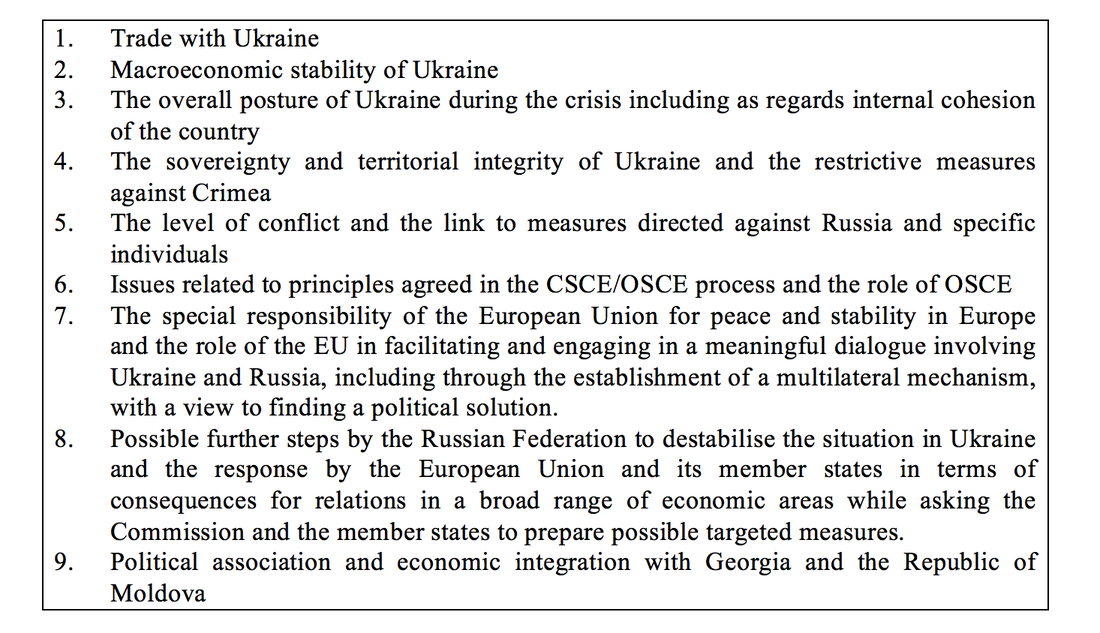

[1] European Council conclusions March 2015 retrieved from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/141749.pdf

- The stated overall objective does in this context not refer to territorial integrity. Further down in the text there is a reference to a condemnation of the annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol by the Russian Federation and a statement that the European Union will not recognise this annexation.

- There is also a reference to de-escalation of the conflict with Russia.

A recent map of the Mariupol line from Reuters

ILLUSTRATION 9.

The terrorist attacks on 9/11 lead to an immediate counterterrorism action plan across the EU pillars. A few years later the 2005 counterterrorism strategy was on the table following the 2003 European Security Strategy and further attacks in Madrid and London.

As a part of this effort an Action plan to prevent radicalization and recruitment to terrorism was adopted in 2005 and updated in 2014 on the basis of a Communication from the Commission.

The main objective of the strategy was “to prevent people from becoming radicalised, being radicalised and being recruited to terrorism and to prevent a new generation of terrorists from emerging”.

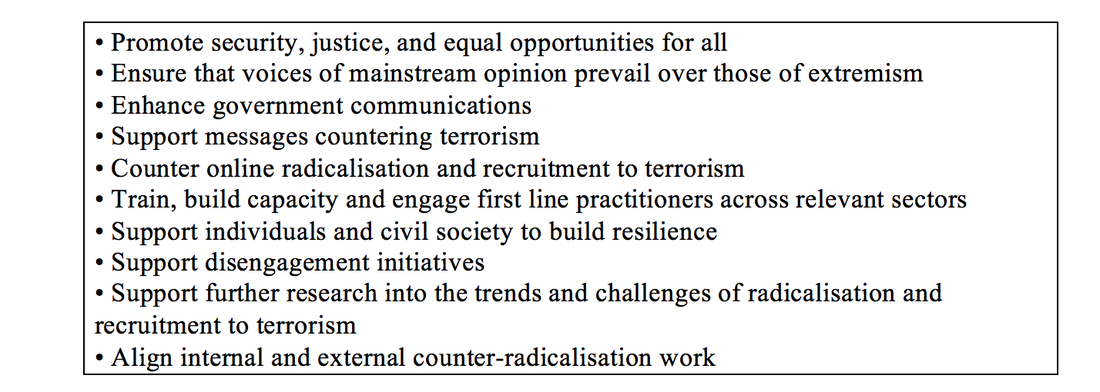

The main commitments of the new strategy were the following:

As a part of this effort an Action plan to prevent radicalization and recruitment to terrorism was adopted in 2005 and updated in 2014 on the basis of a Communication from the Commission.

The main objective of the strategy was “to prevent people from becoming radicalised, being radicalised and being recruited to terrorism and to prevent a new generation of terrorists from emerging”.

The main commitments of the new strategy were the following:

As noted above, the preparatory work for the 2014 update was carried out in the Commission without explicit participation of the EEAS. The descriptive part of the Communication focuses on terrorism in Europe, on European soil, while at the same time mentioning that Europe is directly affected by terrorist activity around the world. Europeans are victims of terrorist attacks outside Europe.

Specific reference is also made to European foreign fighters who could pose a threat to Europe when returning home.

The main approach adopted in the Communication is to explore how the Commission in cooperation with the Council Counterterrorism Coordinator and the High Representative for Foreign and Security policy can assist member states in preventing and countering radicalization more effectively.

The Communication explores in a much more limited way what the EU institutions themselves can do externally. Furthermore, the main emphasis is on what the EU and its member states can do in order to encourage partner countries to take measures of their own.

Reference is made to the need to mainstream radicalization awareness into a series of external assistance instruments including in the area of civil society, education, security and media. In addition there is a reference to multilateral cooperation, more specifically to the Global Counter-Terrorism Forum.

When finalising the revised EU strategy in 2014 member states took several steps in order to broaden the perspective and include the EEAS into the picture.

Inter alia the multilateral approach was considerably developed through the explicit reference to the UN, the Council of Europe, OSCE and again the Global Counter - Terrorism forum.

At the same time it seems obvious that the fact that the Communication was prepared in the Commission with the line DG Home affairs in the lead resulted in something less than a comprehensive approach on the external side.

Specific reference is also made to European foreign fighters who could pose a threat to Europe when returning home.

The main approach adopted in the Communication is to explore how the Commission in cooperation with the Council Counterterrorism Coordinator and the High Representative for Foreign and Security policy can assist member states in preventing and countering radicalization more effectively.

The Communication explores in a much more limited way what the EU institutions themselves can do externally. Furthermore, the main emphasis is on what the EU and its member states can do in order to encourage partner countries to take measures of their own.

Reference is made to the need to mainstream radicalization awareness into a series of external assistance instruments including in the area of civil society, education, security and media. In addition there is a reference to multilateral cooperation, more specifically to the Global Counter-Terrorism Forum.

When finalising the revised EU strategy in 2014 member states took several steps in order to broaden the perspective and include the EEAS into the picture.

Inter alia the multilateral approach was considerably developed through the explicit reference to the UN, the Council of Europe, OSCE and again the Global Counter - Terrorism forum.

At the same time it seems obvious that the fact that the Communication was prepared in the Commission with the line DG Home affairs in the lead resulted in something less than a comprehensive approach on the external side.

Follow-up action after the Paris terrorist attacks in early 2015

The European Council issued a statement after an informal meeting on 12 February 2015. It focused on

• ensuring the security of citizens

• preventing radicalisation and safeguarding values

• cooperation with international partners

It also foresaw a workflow including a proposal from the Commission for a comprehensive European agenda and a further follow-up by the Council in mid 2015.

The Paris attacks resulted in an immediate meeting of justice and interior ministers pledging to further increase counterterrorism efforts in Europe. Significant attention was devoted to improving intelligence, including by again proposing a passenger information network and data exchange with the United States. This was a proposal, which in earlier years had been severely criticized in the European Parliament. It belonged to a category of proposals prevalent after 9/11 aiming at making it possible for different authorities to exchange sensitive data on a new level (case in point: the Patriot Act). It was noted that several of the culprits in Paris were known to the police and had been under surveillance as late as 2014. The United Kingdom and the United States also quickly committed to look into outlawing certain types of encryption.

Several further elements were discussed relating to the Schengen information system; the legal penal framework (cf. the arrest warrant proposal after September 2001); increasing cooperation between Europol and other European agencies including on intelligence; improving sharing of information with law enforcement bodies; reinforcing the information exchange on illegal firearms; improving the fight against financing of terrorism; and promoting cooperation on chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear threats.

All of these issues of course have important external dimensions, which need to be properly elaborated and pursued. But the perspective of radicalisation and recruitment is largely absent from this list.

A search of the EEAS website results in a large number of hits relevant to counterterrorism in external action. But the overall analysis of counterterrorism is almost totally absent. The fact that the Counterterrorism Coordinator is situated in the Council Secretariat is one reason for this. A second is that the staffing devoted to counterterrorism inside the EEAS is limited to just a few officials.

The European Council issued a statement after an informal meeting on 12 February 2015. It focused on

• ensuring the security of citizens

• preventing radicalisation and safeguarding values

• cooperation with international partners

It also foresaw a workflow including a proposal from the Commission for a comprehensive European agenda and a further follow-up by the Council in mid 2015.

The Paris attacks resulted in an immediate meeting of justice and interior ministers pledging to further increase counterterrorism efforts in Europe. Significant attention was devoted to improving intelligence, including by again proposing a passenger information network and data exchange with the United States. This was a proposal, which in earlier years had been severely criticized in the European Parliament. It belonged to a category of proposals prevalent after 9/11 aiming at making it possible for different authorities to exchange sensitive data on a new level (case in point: the Patriot Act). It was noted that several of the culprits in Paris were known to the police and had been under surveillance as late as 2014. The United Kingdom and the United States also quickly committed to look into outlawing certain types of encryption.

Several further elements were discussed relating to the Schengen information system; the legal penal framework (cf. the arrest warrant proposal after September 2001); increasing cooperation between Europol and other European agencies including on intelligence; improving sharing of information with law enforcement bodies; reinforcing the information exchange on illegal firearms; improving the fight against financing of terrorism; and promoting cooperation on chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear threats.

All of these issues of course have important external dimensions, which need to be properly elaborated and pursued. But the perspective of radicalisation and recruitment is largely absent from this list.

A search of the EEAS website results in a large number of hits relevant to counterterrorism in external action. But the overall analysis of counterterrorism is almost totally absent. The fact that the Counterterrorism Coordinator is situated in the Council Secretariat is one reason for this. A second is that the staffing devoted to counterterrorism inside the EEAS is limited to just a few officials.

ILLUSTRATION 10.

Some generic questions for the impact assessment ex ante:

· How to fighting causes rather than symptoms.

· Adopting a long time perspective both earlier in time and towards the future.

· Looking towards the totality of EU member state actions not only in specific regions but globally and functionally.

· Addressing capacity issues upstream from the present concrete proposals for instance in the Syria-Iraq-ISIS communication or the ENP progress report on Ukraine.

· Discussing who should do what in the international community

· Discussing requirements in order to enable those actors to function effectively

· With whom should policy dialogue be pursued?

· What should be the programme of action for instance in the dialogue with United States? Should and could the European Union and or member states engage with key international actors notably the Russian Federation and in the radicalisation case with Iran?

· What should be the role of religious and political leaders outside government?

· How to fighting causes rather than symptoms.

· Adopting a long time perspective both earlier in time and towards the future.

· Looking towards the totality of EU member state actions not only in specific regions but globally and functionally.

· Addressing capacity issues upstream from the present concrete proposals for instance in the Syria-Iraq-ISIS communication or the ENP progress report on Ukraine.

· Discussing who should do what in the international community

· Discussing requirements in order to enable those actors to function effectively

· With whom should policy dialogue be pursued?

· What should be the programme of action for instance in the dialogue with United States? Should and could the European Union and or member states engage with key international actors notably the Russian Federation and in the radicalisation case with Iran?

· What should be the role of religious and political leaders outside government?

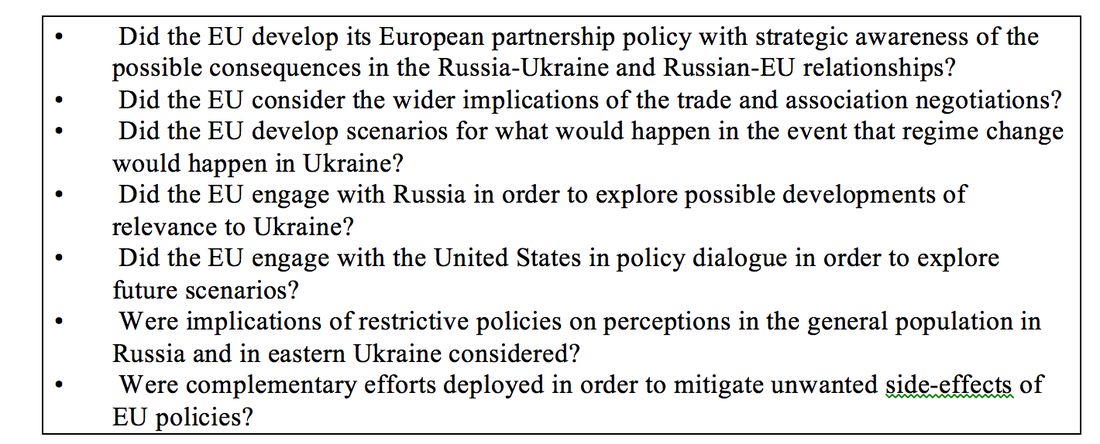

Illustration 11. Examples of evaluation questions to be put ex post in the Ukraine case:

ILLUSTRATION 12. Illustration of questions to be put in the evaluation of earlier EU counter-radicalization efforts

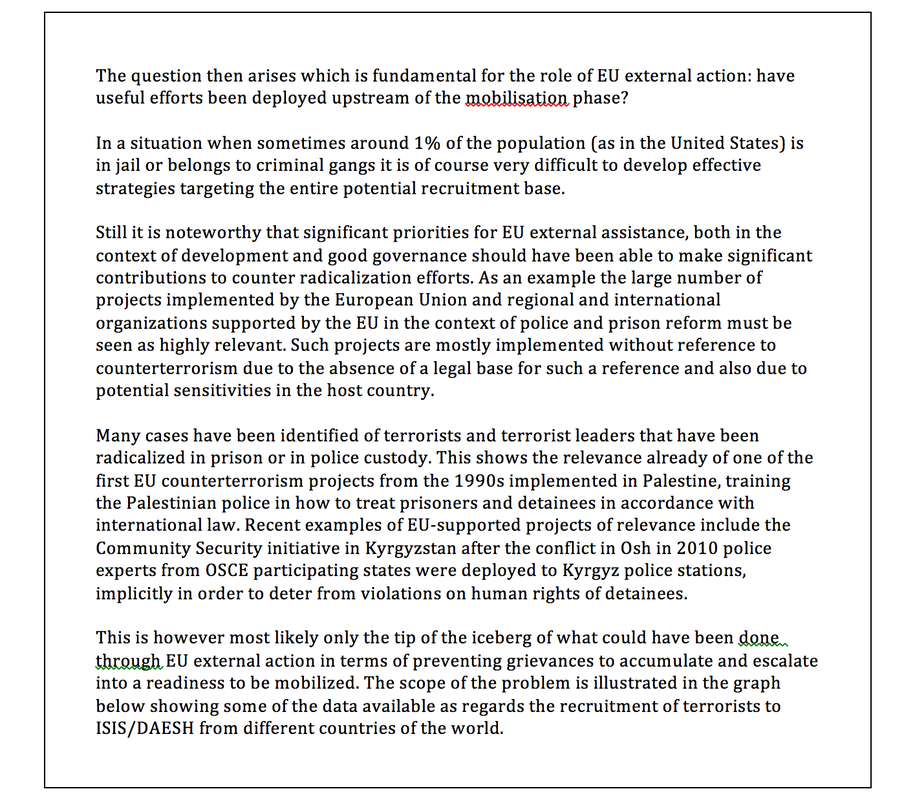

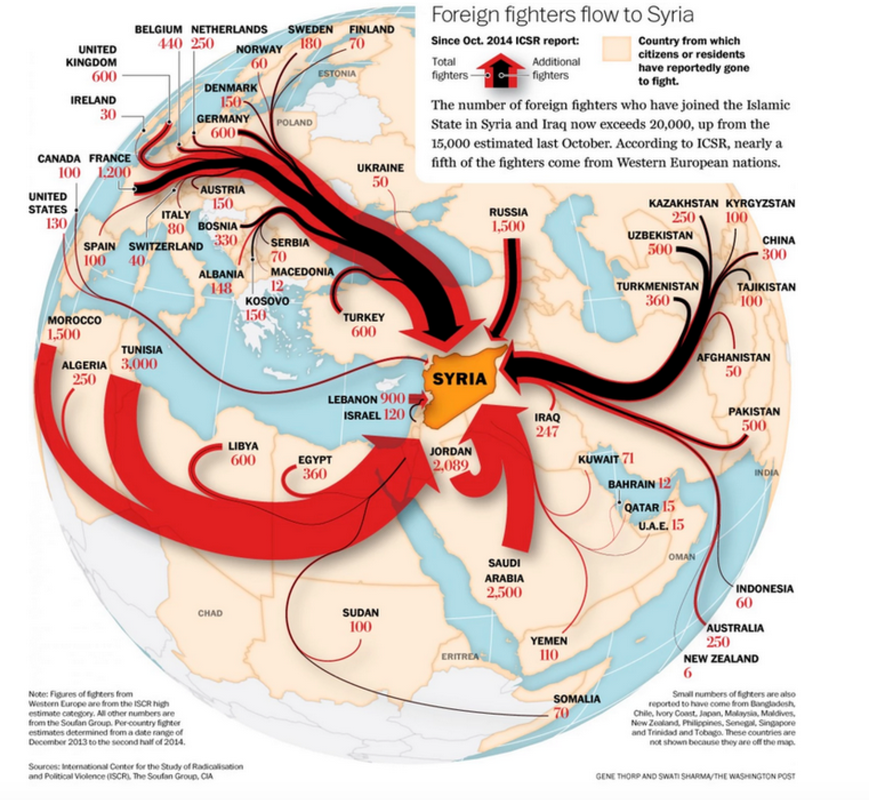

Flows of ISIS warriors to Syria according to the Guardian:

And some forward-looking questions:

The question is to what extent it is possible for Europe to enhance its communication and education policies externally in order to counteract the tendency to feel alone with the only alternative to align with aggressive ideological communities?

Around the recent summit in Washington countering violent extremism there were a large number of seminars dealing with this problem including discussing role models. But what more can be done in this domain? Should the EU do more in order to model its restrictive policies, conditionality policies, etc. in order to promote an image of the EU as a force for good globally?

To what extent should such considerations influence the EU strategic review?

The question is to what extent it is possible for Europe to enhance its communication and education policies externally in order to counteract the tendency to feel alone with the only alternative to align with aggressive ideological communities?

Around the recent summit in Washington countering violent extremism there were a large number of seminars dealing with this problem including discussing role models. But what more can be done in this domain? Should the EU do more in order to model its restrictive policies, conditionality policies, etc. in order to promote an image of the EU as a force for good globally?

To what extent should such considerations influence the EU strategic review?

Towards a strategic planning capacity in EU external action of relevance to radicalisation and recruitment

Terrorism and organised crime are interconnected in a way not totally realised in the counterterrorism discourse before 9/11. The links between internal and external aspects of security have been demonstrated by globalization, resulting in both positive and negative flows, human, material, financial, virtual. It is clear that the current subdivision of EU external action policies into different geographic areas, even if pursued on the regional level, will not in itself be sufficient to cover the relevant aspects.

As an example it is noteworthy that the recent joint communication from the Commission and the EEAS on Syria, Iraq and Isis/Daesh required cooperation between two separate geographic departments in the EEAS.

Currently, the horizontal and thematic capabilities of the EEAS are very limited. This also means that the liaison function with the Commission's thematic departments is weak.

Terrorism and organised crime are interconnected in a way not totally realised in the counterterrorism discourse before 9/11. The links between internal and external aspects of security have been demonstrated by globalization, resulting in both positive and negative flows, human, material, financial, virtual. It is clear that the current subdivision of EU external action policies into different geographic areas, even if pursued on the regional level, will not in itself be sufficient to cover the relevant aspects.

As an example it is noteworthy that the recent joint communication from the Commission and the EEAS on Syria, Iraq and Isis/Daesh required cooperation between two separate geographic departments in the EEAS.

Currently, the horizontal and thematic capabilities of the EEAS are very limited. This also means that the liaison function with the Commission's thematic departments is weak.