|

There are strong indications that not least from an EU perspective the implications were to some extent devastating and to some extent beneficial. How is this possible?

– clearly 9/11 dealt a serious blow to those in the EU who saw security as a purely intergovernmental issue to be dealt with in the context of the military part of the European Security and defence policy. The European Council immediately ordered an across-the-board inventory of all possible contributions to counterterrorism. The fact that perhaps even the main attention was given to Justice and home affairs also led to the strong growth of that sector of cooperation in the EU in the following decade. A few years later the focus on radicalisation also illustrated the links to development policy. - the devastating effect was by no means inevitable, it was a result of deliberate choices by the first George W Bush Administration to focus on a quick military victory in Iraq followed by a decade of reckless radicalisation not least of the Sunni population in Iraq. This in turn led also EU leaders to forget what had been an important discourse before 9/11 namely conflict prevention. This is one of the findings of a serious evaluation made of conflict prevention policies in the last decades.

1 Comment

First: Can the EU be a force for good in international relations? Those who observe the possible endgame in the Iran nuclear negotiations would say yes although the notion of " a force for good" perhaps gives the wrong image of the EU role. This is not hard power on the part of the EU, it is soft power helping to open doors rather than to close them.

This is therefore also a good example of how the potential influence of the EU on security often is systematically underestimated. Second: The Iran case illustrates the need for a comprehensive approach. The nuclear negotiations form part of a functional approach to security, horizontal WMD proliferation which is discussed in the thematic heading in this website and in my forthcoming book on the EU and security. At the same time it is an important part of the discourse on the role of Iran in the regional geographic context, including Israel –Palestine and the conflict in the wider Middle East as discussed in the geographic chapter of this website and in the book. Essentially, the notion that the devil is in the detail needs to be complemented with the fundamental notion that progress on security requires strategic overview as discussed in the strategy chapter of the website and the book. Grievance - ideology - mobilisation -- those are the three generally recognised stages.

The role of ideological leaders, political or religious are key in the 2nd and third stages. Legally they may do no wrong, but in reality they may provide the human resources necessary for terrorist acts. Their social networks are no doubt a key target for today's intelligence efforts. But if we want to intervene at an earlier stage we have to address grievances. Indeed we should not counter propaganda with propaganda as discussed in the Economist. Optimistic cover story about Isis. Help is first and foremost coming from Iran to the Shia part of Iraq. Brzezinski worried about Russia mentioning nuclear weapons. German defence minister L says not to underestimate military readiness as regards the Baltic states. B: Risk that Western aid to Ukraine will not be effective L very high costs t. Russia Also sustainable growth in German defence budget. Close to 4 percent more next year. Slow decision-making in NATO? B. Maybe but wait for the US to react... L. And economic sanctions do hurt. B. But Russian action may provoke collapse of Ukrainian economy. L on European army: good to have common labour market - so for defence we can also do more within the framework of the Lisbon treaty. The French German brigade is in Mali. Need to strengthen Tunisia. B. Russia global danger in the sense of producing threats which might damage. Issue not just in terms of Ukraine.Joint interest to resolve. Well maybe with filled refrigerators. But otherwise perhaps not. Or what do you think? 1. From the military, and notably, a NATO perspective, there is a perceived window of danger until the decisions of the Wales Summit have been implemented and Russia denied what is called escalation dominance. Until this is the case (in combination with the ongoing readjustment of defence policies in Sweden, Finland and other non-NATO states) there is a widespread perception that Russia may continue aggressive behaviour also west of Ukraine.

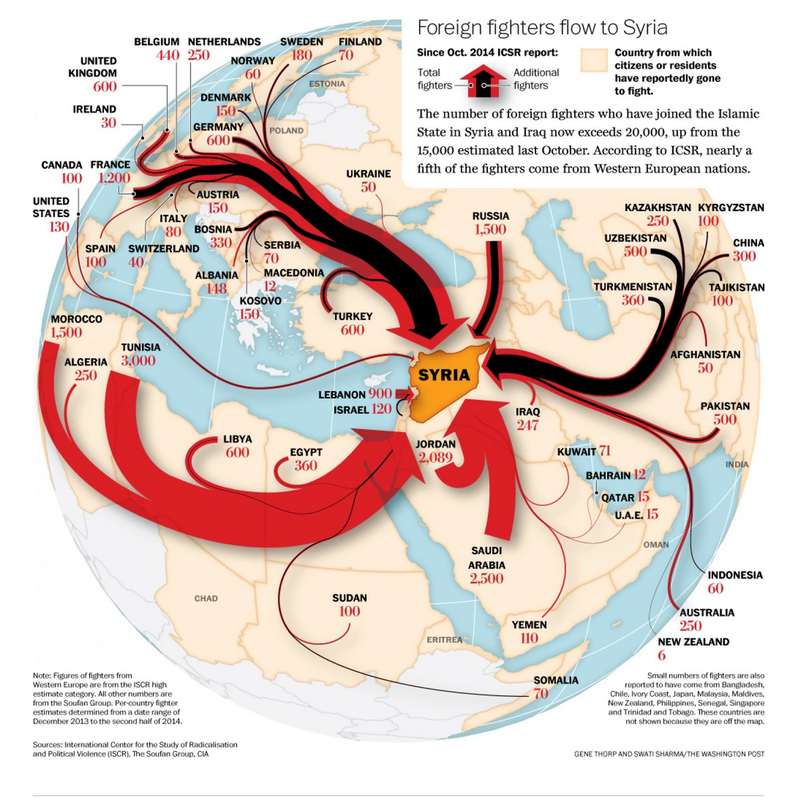

2. From an economic perspective, it is now evidently clear that the combined effect of restrictive policies, the lowering of the oil price and the general lack of engagement with Russia on the side of the West is having devastating consequences for Russian economy. A breaking point may come in a couple years. So far the Russian population is overwhelmingly supporting the official nationalistic policies. But this could change quickly. To quote Richard Swartz: the population may turn their attention from the television set to the refrigerator. Would Russia in such a situation try to project even more strongly an external threat perception in order to increase unity in the country? Already the possibility of such a development must be taken into account - now. Against this background it would seem that the overarching objective of the German and French leaderships is to gain time by trying to engage with Moscow to come through the coming period without turmoil. The posture of the new president of the European Council Tusk, who is likely to take a strong role on the EU level, is going to be very important in this context. Those who are trying to purely isolate Russia may be asking for real trouble from both of these perspective. Instead there is a need to engage with Russia also on the multilateral level, including notably the OSCE. The West is strongly dependent on mutually beneficent cooperation with a stable Russia in the long run. Russia is a global nuclear power. And the humanitarian aspect is already becoming very prominent. Millions suffer in Ukraine and beyond. To be continued - to be sure.  (Photo AP) I will in the coming days and weeks submit a number of comments to the proposed elements for a regional strategy on Syria, Iraq and ISIS/DAESH put forward by the High Representative Mogherini and the European Commission in a communication dated 5 February 2015. This is one of the first examples of what the new leadership would see as a comprehensive approach to external conflicts and crises. Three questions arise: First, does it cover the scope of the current international debate? And secondly, from an EU perspective: does it cover the relevant policy perspectives in EU security policy outlined in the handbook on EU and security which I will publish shortly, based upon many interviews inside the institutions. Third: The EU tried once before in 2013 to put forward a communication on Syria labelled a comprehensive approach to the crisis. To what extent does the new communication represent progress in terms of comprehensiveness? On the issue of the international discourse, a number of detailed presentations of the discussion are available on the web. For the purpose of the discussion of an EU strategy to the crisis a relevant contribution has recently been made by Amir Madani, Huffington Post. In brief, he makes links not least to the following main issues which he characterises as tactical and strategic: -- Military presence to limit the expansion of terrorist acts -- Recognition and engagement with the institutions of the regimes currently in place -- Negotiations with current Syrian institutions -- Iran and the resolution of the WMD issue. -- The resolution of the Palestine Israel issue -- Turkey and its relationship to Europe -- Support to the Iraqi government including in enacting major reforms promoting more inclusiveness. -- Possible regional conference under the auspices of the UN Security Council and including the United States, Europe, China, Russia, and important participation by Iran, Turkey, Egypt and Saudi Arabia. -- Supporting civil society throughout Arabia To what extent does the European Union in its approach to the region include these various elements - and others - into the analysis of its potential comprehensive approach? This I will try to explore in one on my following blog posts in pursuit of an enhanced EU comprehensive approach to external conflicts and crises. The proof of the pudding - after all - is to be found in concrete case studies. That this is a crucial discourse also for the internal security of the EU should not least be obvious from the graph below published recently in Washington Post: It is quite noticeable: this was a speech about European interests being in line with member states interests: "No member state can do it alone." More than a dozen references were made to interests, only a single on to values.

This was also a speech focusing on hard and soft power in the non-military sphere: "Military force is at times necessary, but never sufficient." She does not mention NATO and she does not mention CSDP. Instead she focusses on the importance and impact over time of sanctions. I personally welcome the point made on hope as an element of soft power, essential to understand why the power of attraction of the EU has been larger-than-life in several neighbouring countries. She rejects the notion of clash of civilisations which she describes as fabricated: "the clash runs within our civilisations not between them". The Arab and Moslem countries are the first targets of terrorism. The Fortress Europe idea is described as a very naive illusion. In the question-and-answer session she predictably notes that she had not been able to speak about everything, notably not on Turkey, not on the Balkans. Still the priorities in her speech were clear. The fact that Afghanistan was not mentioned was probably not a coincidence. The fact that she hardly mentions the defence policy discussion will probably be remedied in later speeches. But it still says something about the profile of the new HR/VP and the way it reflects the mood among EU foreign and possibly also defence ministers. Integrating the common security and defence policy into the CFSP is more difficult than ever over the last decade. She does refer to a comprehensive approach to foreign policy, but not to the comprehensive approach to external conflicts and crises as set out in the joint communication by the HR/VP and the Commission towards the end of 2013. She clearly has embraced the broader approach advocated by some member states moving beyond the situation in the fragile regions of Africa to an emphasis on the wide range of security-related instruments required to deal with the neighbourhood problems. In so doing, her reference to a number of key community policies such as education and employment indicate a shift from an intergovernmental comprehensive approach to a community-based coherence approach as outlined in not only the Lisbon but also earlier treaties. She may expect some criticism from her Foreign Minister colleagues on this point. Many have asked her to work more closely with the Commission than Ashton did. The proof of the pudding will however be to what extent member states will allow the cooperative framework no agreed in the form of clusters in the Commission to become of real substantive importance. |

Archives

May 2015

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed